When I started my time at the University of California Irvine, I was looking for some early engineering experience. I decided to enroll in a class known as Engineering 7A. It is a project class where teams would work together to build rovers for a final competition. I was eager and ready to get started on an engineering project. Unfortunately, there was a complication. The year was 2020, the pandemic raged, classes were online and parts nigh inaccessible. When my team was formed, necessity pushed us to adapt.

I was placed in a team with three other student engineers who shared a passion for engineering. We quickly realized that we needed a reliable method of communication, so we used a text server on discord to coordinate our efforts. Further, we needed to develop an identity. We chose to name ourselves Team Work In Progress, to symbolize that we were still engineering students pushing to build a rover. Once these matters were settled, it was time to organize the team.

The team was provided four roles which we had to fill. They were the researcher, the SolidWorks specialist, the documenter and the team captain. My team nominated me as the team captain to organize the team and make sure that our rover would be completed on time. To make sure of this, I split SolidWorks responsibilities across the team. Instead of one person being responsible for modeling the entire rover, four roles were created. One person was responsible for the steering mechanism, another was to create the chassis. A third worked on attaching the battery to the frame and I was responsible for the gear guard and motor mount.

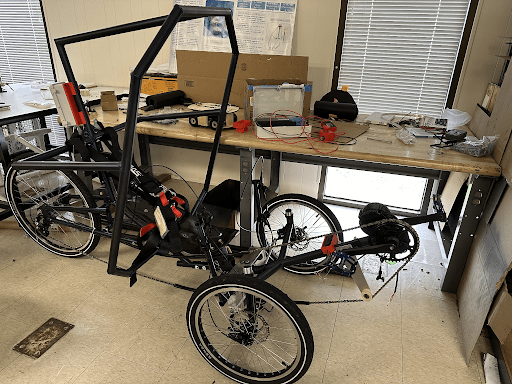

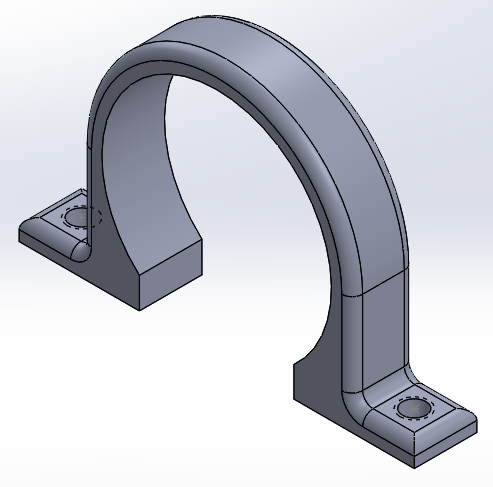

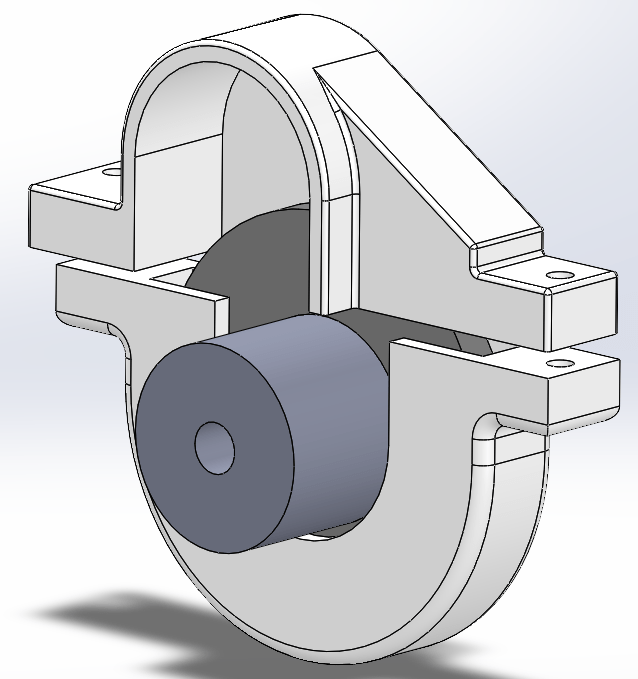

The gear cover and motor mounts I developed went through several iterations. My first motor mount was a solitary loop which used only friction to hold the motor. The first gear cover was a large sheath which had a large hollow compartment to hold the two man gears and a secondary extension which protected the motor’s axel from the outside.

Figure 1: The first version of the rover’s motor mount.

Figure 2: The first version of the gear cover.

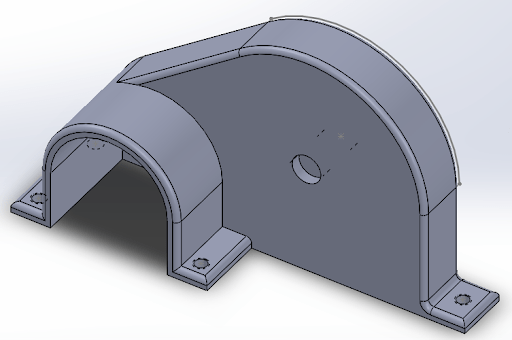

Both of these parts changed substantially during development. The motor mount underwent major changes. Instead of a loop to hold the motor in place with friction, I decided to take advantage of four mounting holes in the motor. To do this, I designed a plate with four unobtrusive mounting holes aligned with the holes in the motor. Additionally, I created two arms which went under the motor to support it and keep it level.

Figure 3: The final version of the rover’s motor mount. Note that the motor has been made transparent to show the supports.

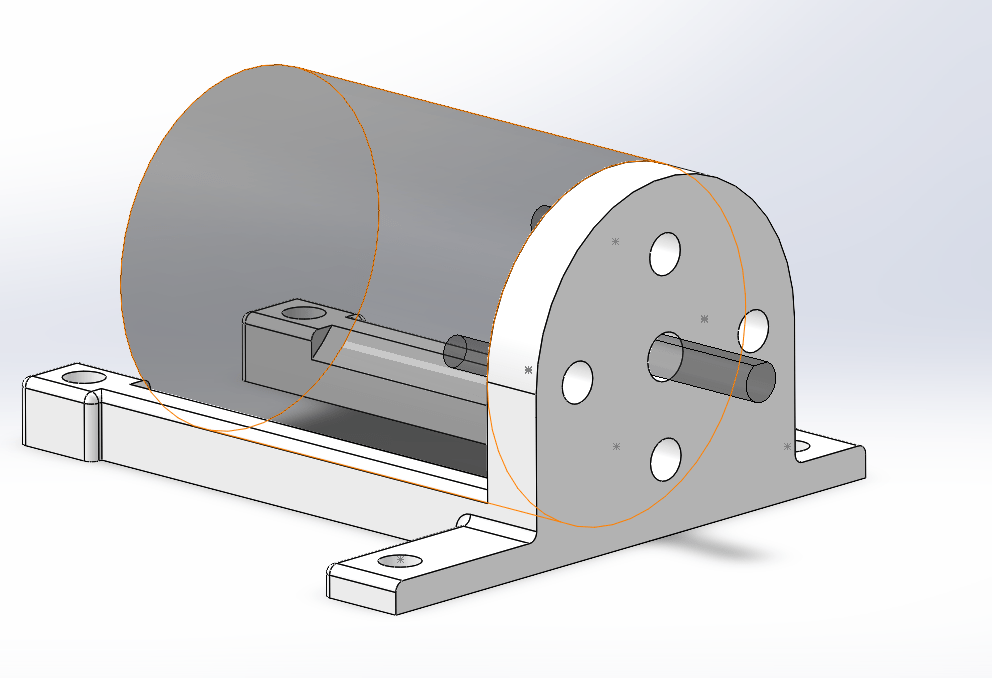

The gear guard also changed radically during the design process. The motor’s axel was placed below the top half of the chassis. As a result, it was necessary to split the gear guard into two parts. The upper gear guard protected the motor’s axel and the connection between the drive gear and the driven gear. Its extension slides smoothly onto the motor. The lower gear guard protected the driven gear from the outside environment. There is a hole in the lower gear guard to accommodate the gear hub. The upper and lower gear guards are shown at a distance from each other to accommodate the chassis. The design of the motor mount and gear guard was completed in the first five weeks of the quarter.

Figure 4: The gear covers shown with the driven gear. The lower gear guard has a large hole in it to accommodate a gear hub.

Figure 5: A side view of the completed computer gear guard and motor mount.

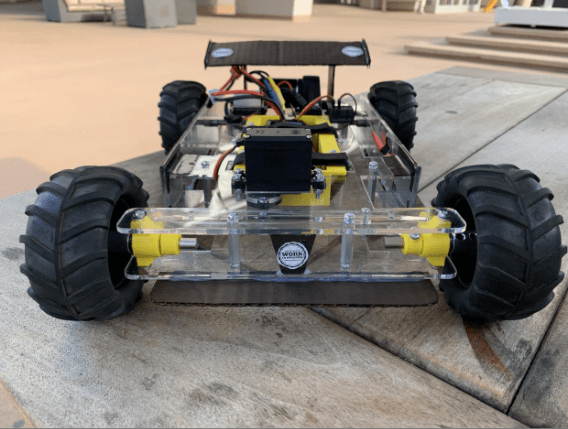

Once the design of the rover was completed, the task switched to assembling it. This was complicated by the pandemic. While classes were entirely online, I lived in the college dorms during this quarter. Another team member also lived on campus during this time. Due to this, the rover was assembled on campus. Me and Hudson worked together to complete the rover before the end of the quarter.

At the end of the course, the instructors released the dimensions of a simple track shaped like a figure eight that all the teams needed to complete in order to receive full credit. Due to the popularity of the course, the student body was ultimately split into 47 teams of 4. Each of these teams attempted the course, completing time trials before submitting their shortest lap. Of the teams, 8 failed to complete the course while two other teams failed to properly understand the time trial. From the remaining 37 teams, there could be only one victor. My team, Team Work In Progress, completed the course in 21.05 seconds. This time was 1.45 seconds faster than second place and 1.78 times faster than the average rover.

After I learned that our team won, I realized that our team needed to continue working together. The team acted in concert to engineer a highly effective rover which secured victory against 46 other teams. Therefore, it was natural to ensure that our team would continue to work together during the follow up course, Engineering 7B. I coordinated my team members to all register for the same class sections, so we could continue to act as a cohesive team and reuse parts of our highly successful design.

Figure 7: Our team’s complete rover.