Mars has long been the premier destination of robotic space probes searching for life. The space programs of America and China currently aspire to send a crew to Mars. Furthermore, SpaceX has committed itself to sending Starships to Mars as soon as physically possible. All of these efforts rely on a standard trajectory known as the Hohmann transfer orbit. I wanted to determine there was a sometimes superior alternative by comparing a Hohmann transfer orbit to a Lunar Gravity Assist launched under ideal circumstances. I determined that a Lunar Gravity Assist is superior because it uses 3.7% less delta-v.

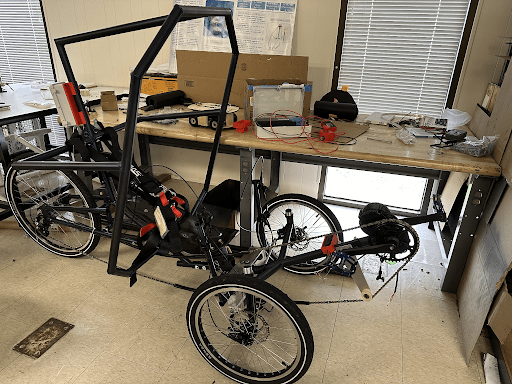

The standard way spacecraft are launched from Earth to Mars is via a Hohmann transfer orbit. A Hohmann transfer orbit’s trajectory is an ellipse which barely touches both the initial and final orbit. It is standard because it is the most efficient trajectory whenever two conditions are met. The radial distance between the initial and final orbit is small and there must not be other massive objects which can provide energy to the spacecraft.

Figure 1: An idealized Hohmann transfer orbit. Image Credit: https://rantonels.github.io/capq/q/OM2.html

Massive objects can provide orbital velocity to a spacecraft in what is known as a gravity assist. A spacecraft passes close to an object and changes direction during the passage. While the spacecraft’s velocity relative to the object does not change, its overall velocity may change. This occurs because part of the object’s orbital velocity is added or subtracted from the spacecraft’s velocity. This is an exchange of momentum and the object’s orbit is changed by an equal force. Since the object is so much larger and more massive than the spacecraft, this orbital change is negligible. Only massive objects can provide gravitational forces sufficient to change the orbit of spacecraft, with the Moon being barely large enough to provide a substantial gravity assist. I wanted to see how useful this assist could be when simulated under ideal circumstances and coded a program in MATLAB to see if a lunar gravity assist provided substantial gains.

Figure 2: A NASA rendering of Mars rising over the Lunar surface, representative of the Moon to Mars program architecture. Image Credit: NASA https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/new-program-office-leads-nasas-path-forward-for-moon-mars/

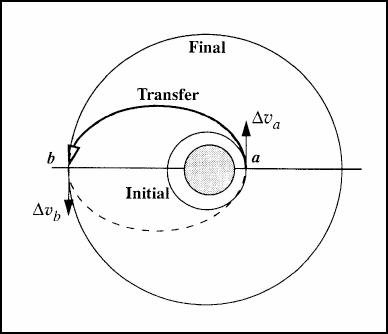

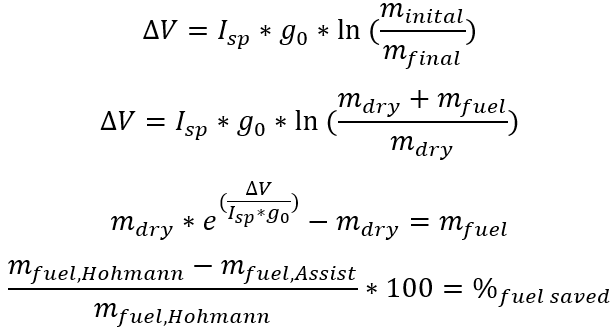

I divided my program into three sections, an introduction, a main code and a system which graphs the results. The introduction sets constants and starting positions, the body simulates trajectories and the conclusion graphs relevant results.

Several measures were taken to optimize the program and make it easier to find optimal trajectories. I neglected the force between Mars and the Earth along with the force between Mars and the Moon. Furthermore, I made the orbits of the Moon and Mars perfectly circular and 2 dimensional to make it easier to adjust the phase angle of the Moon and Mars. I decided to use Euler’s approximation instead of patched conics to simulate the trajectory since I believed that Euler’s approximation with a time step of 1 second would be more accurate than patched conics. To ensure that optimal trajectories were achieved, a function which computed the angle difference between the spacecraft’s velocity and the Earth’s velocity was included.

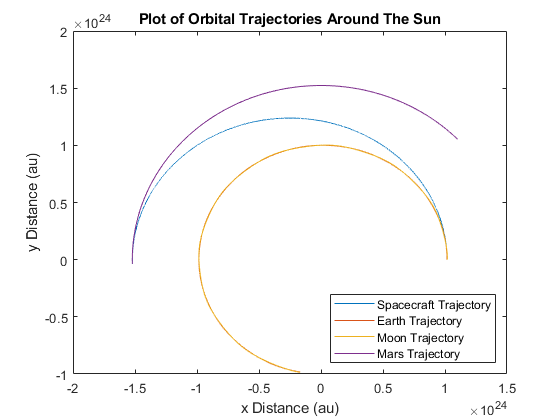

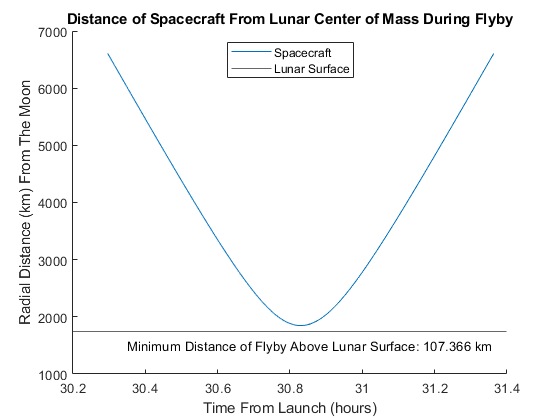

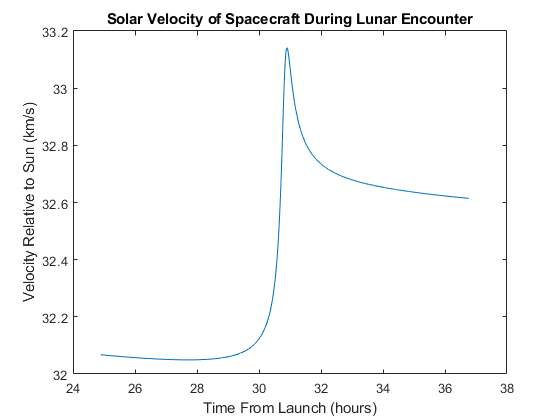

The final section of the program produce graphs which showcase the results of the program. For both scenarios, the program creates a graph of every trajectory and a plot of the spacecraft’s distance from Mars. This demonstrates that the spacecraft successfully traveled to Mars and passed close to its surface. If a Lunar Gravity Assist to Mars is simulated, the code also plots the spacecraft’s distance from the Moon and its velocity relative to the Sun during the lunar gravity assist. This demonstrates that a Lunar Gravity Assist occurred and it caused the spacecraft’s velocity to significantly increase.

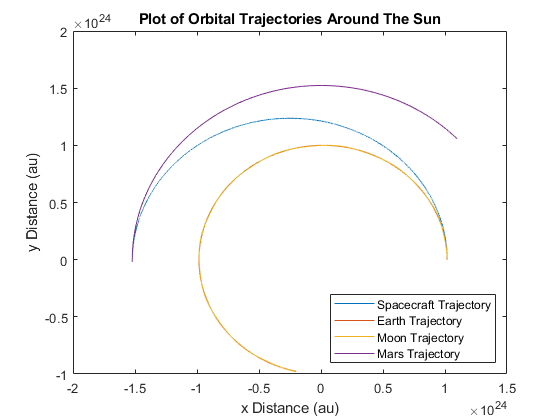

Figure 3: A plot of orbital trajectories in a scenario where a standard Hohmann Transfer orbit is used to reach Mars.

Figure 4: A plot of orbital trajectories for the scenario where a Lunar Gravity Assist is used to reach Mars.

The delta-v, or change in the spacecraft’s velocity, was computed by subtracting the orbital velocity of a spacecraft in a 500 km circular parking orbit from the orbital velocity of the spacecraft. For the Hohmann Transfer, the required delta-v was 3580 meters per second. For the Lunar Gravity Assist, the required delta-v was 3447 meters per second. Compared to the Hohmann Transfer, the Lunar Gravity Assist saved 133 meters per second of delta-v.

I found that a Lunar Gravity Assist uses approximately 5.68% less fuel compared to a Hohmann transfer orbit under ideal circumstances. I calculated this percentage using the SpaceX Raptor engine’s specific impulse of 380 seconds and the standard gravity of 9.806 meters per second squared.

To find the percentage of fuel saved, I calculated the fuel mass in terms of the dry mass for both the Hohmann Transfer and the Lunar Gravity Assist. Then, I found the difference between the two fuel masses, divided that by the Hohmann fuel mass, multiplied by 100 and retrieved the percentage of fuel saved.

Figure 5: Set of equations I used to determine the percentage of fuel saved. The first three equations are all manipulations of the rocket equation. The fourth equation is the equation needed to find a percentage applied to this calculation.

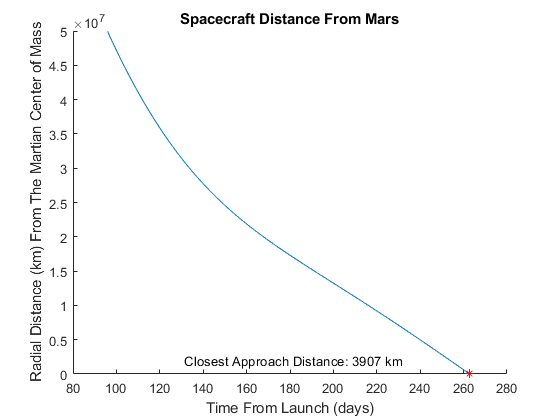

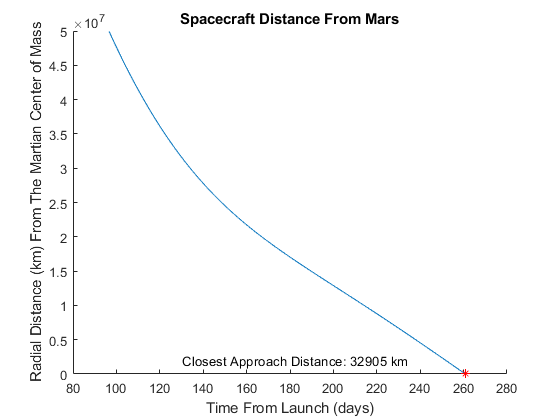

I verified my trajectory by creating graphs which chart the spacecraft’s distance from Mars in both scenarios. Furthermore, I created two graphs for the Lunar Gravity Assist scenario which display the spacecraft’s distance from the Moon and Solar velocity during the Lunar flyby.

Figure 6: The spacecraft’s distance from Mars on a classic Hohmann Transfer Orbit. The closest approach occurred at a minimum distance of 3907 km.

Figure 7: The spacecraft’s distance from Mars after a Lunar Gravity Assist. The closest approach occurred at a distance of 32905 km.

For both flybys of Mars, the spacecraft approaches quite close to Mars. While the Hohmann Transfer Orbit passed much closer to Mars compared to the Lunar Gravity Assist, both encounters are within Mars’s sphere of influence and demonstrate a successful transfer.

Figure 8: The distance of the spacecraft from the Lunar Surface during the closest period of the Lunar Gravity Assist.

Figure 9: The velocity of the spacecraft relative to the Sun during the Lunar Gravity Assist.

Inspecting the charts which show the spacecrafts distance and velocity during the Lunar flyby, I can determine that the spacecraft passed close to the the Lunar surface and gained velocity relative to the sun during the Lunar Gravity Assist. These results indicate that the gravity assist is physically possible and had the desired effect of increasing the spacecraft’s velocity. This data validates the proof of concept.

In summary, I found that a Lunar Gravity Assist under optimal circumstances is superior to a Hohmann Transfer Orbit. The Gravity Assist used 133 fewer meters per second or 3.7% less delta-v compared to a standard Hohmann Transfer. If the spacecraft is propelled by a SpaceX Raptor engine, the delta-v savings lead to a 5.68% reduction in fuel consumption.